New Research Reveals How Tattoos Can Alter the Immune System

Last updated on

Tattoos have become so widespread that they are often treated as a routine cosmetic choice rather than a biological event. From minimalist wrist designs to full sleeves, body art now spans generations and lifestyles, rarely raising concern beyond aesthetics or personal meaning. Yet while the symbolism of a tattoo is usually clear to the person wearing it, the biological consequences are far less visible and far more complex. Once tattoo ink enters the body, it does not simply sit quietly beneath the skin. It becomes part of living tissue that responds, adapts, and remembers, even long after the surface has healed. Beneath the skin, tattoo pigments interact with the immune system in ways scientists are only just beginning to understand. Tattoos are generally considered safe, but growing scientific evidence suggests tattoo inks are not “biologically inert.” The key question is no longer whether tattoos introduce foreign substances into the body, but how toxic those substances might be and what that means for long-term health. Tattooing introduces chemical compounds into tissue that was never designed to store them for decades, raising concerns about immune activation, inflammation, and cumulative exposure that may only become apparent over time.

What tattoo ink is actually made of

Tattoo inks are complex chemical mixtures rather than simple dyes. They contain pigments that give color, liquid carriers that help distribute the ink into the skin, preservatives to prevent microbial growth, and small amounts of impurities that arise during manufacturing. Many pigments currently in use were originally developed for industrial applications such as car paint, plastics, and printer toner, not for injection into human skin. Once introduced into the body, these substances become long-term residents in living tissue. Some tattoo inks contain trace amounts of heavy metals, including nickel, chromium, cobalt, and occasionally lead. Heavy metals can be toxic at certain levels and are well known for triggering allergic reactions and immune sensitivity. Even low-level exposure can irritate tissues and stimulate immune responses that do not always appear immediately. This delayed reaction helps explain why some tattoo-related symptoms surface months or even years after the tattoo is applied, long after the initial healing period has passed. Tattoo inks can also contain organic compounds such as azo dyes and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Azo dyes are synthetic colorants widely used in textiles and plastics, and under certain conditions such as prolonged sun exposure or laser tattoo removal, they can break down into aromatic amines. These chemicals have been linked to cancer and genetic damage in laboratory studies. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, commonly found in soot and vehicle exhaust, are often present in black inks made from carbon black, and some are classified as carcinogenic.

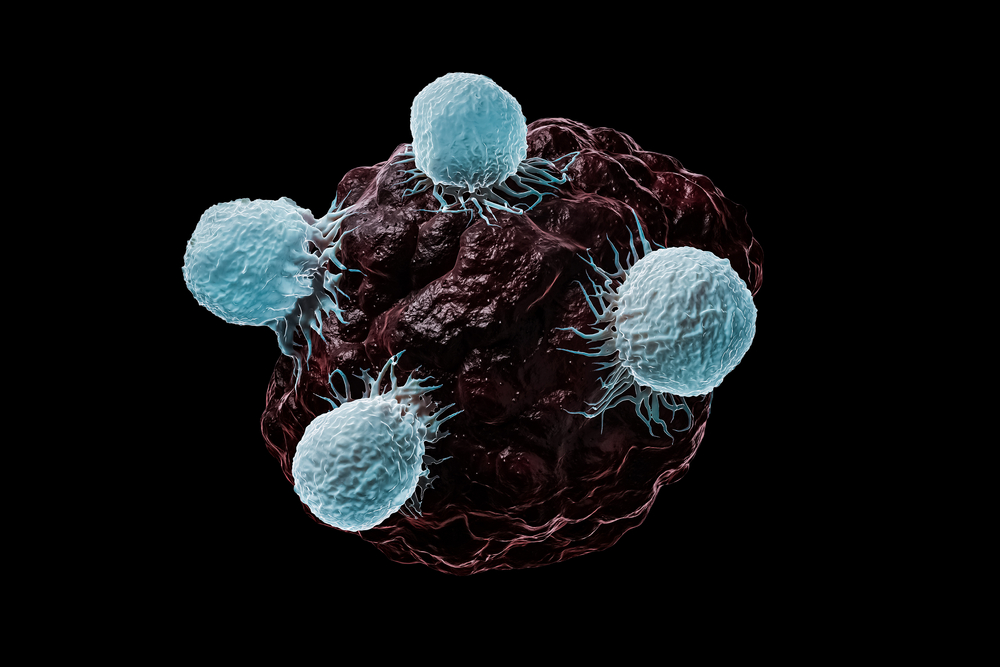

How the immune system responds to tattooing

Tattooing involves injecting ink deep into the dermis, the layer of skin beneath the surface that contains blood vessels, nerve endings, and immune cells. The body immediately recognizes pigment particles as “foreign material.” Immune cells attempt to remove them, but the particles are too large to be fully cleared. This triggers a unique biological response that allows the ink to remain visible for life.

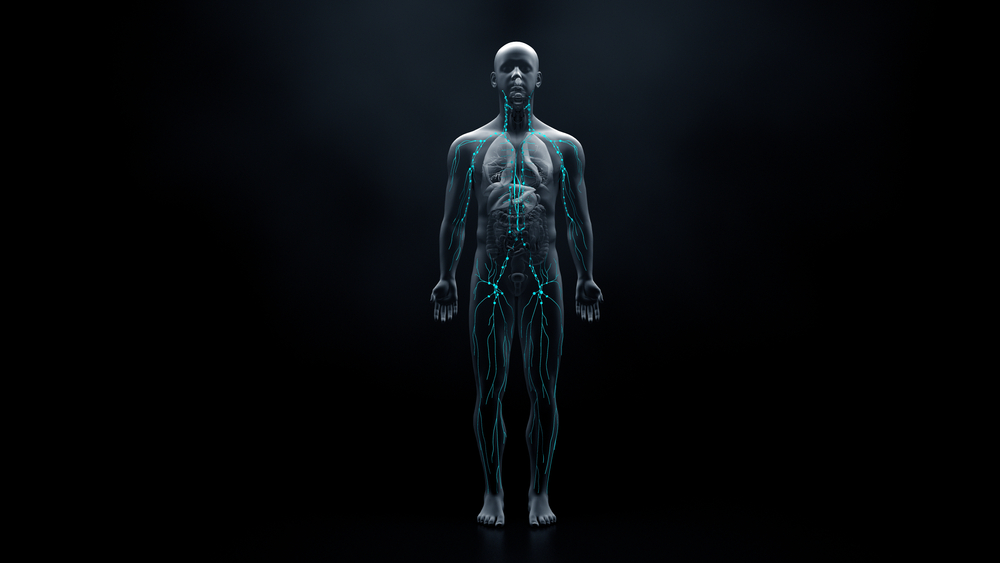

Why tattoo ink does not stay in the skin

Tattoo ink does not remain confined to the tattooed area. Studies show that pigment particles can migrate through the lymphatic system and accumulate in lymph nodes. Lymph nodes are small but vital structures that filter immune cells and help coordinate immune responses throughout the body. They play a central role in detecting threats and organizing defense mechanisms. Researchers have detected tattoo pigments, including heavy metals, inside lymph nodes located far from the original tattoo site. This means tattoos are not just a localized skin change but a form of systemic exposure. The long-term health effects of ink accumulation in lymph nodes remain unclear, but their role in immune regulation raises concerns about prolonged exposure to metals and organic toxins within these tissues. Because lymph nodes are deeply involved in immune signaling, any disruption or chronic exposure within them has the potential to influence immune behavior elsewhere in the body. This area remains under active investigation, particularly as tattoos become larger, more numerous, and more colorful.

Tattoos, inflammation, and immune signaling

Recent research suggests that commonly used tattoo pigments can influence immune activity beyond the skin. Tattoo ink is taken up by immune cells, and when these cells die, they release signals that keep the immune system activated. Researchers observed that this process can lead to inflammation in nearby lymph nodes lasting for up to two months after tattooing. The same study found that tattoo ink present at a vaccine injection site altered immune responses in a vaccine-specific way. Notably, it was associated with a reduced immune response to the COVID-19 vaccine. This does not mean tattoos make vaccines unsafe. Rather, it suggests tattoo pigments can interfere with immune signaling, the chemical communication system immune cells use to coordinate responses to infection or vaccination, under certain conditions.

Color, chronic reactions, and long-term inflammation

Coloured inks, particularly red, yellow, and orange, are more frequently associated with allergic reactions and chronic inflammation. This is partly due to metal salts and azo pigments that can degrade into potentially toxic aromatic amines. Red ink is especially known for causing persistent itching, swelling, and granulomas. Granulomas are small inflammatory nodules that form when the immune system attempts to isolate material it cannot remove. These reactions may appear months or even years after a tattoo is applied and can be triggered by sun exposure or changes in immune function. In some cases, symptoms persist despite medical treatment. Chronic inflammation is not limited to discomfort or cosmetic concerns. Long-standing inflammatory processes have been linked to tissue damage and increased disease risk over time. For people with autoimmune conditions or weakened immune systems, tattoos may pose additional concerns that warrant careful consideration before getting inked.

Infection risks and lack of regulation

Like any procedure that punctures the skin, tattooing carries some risk of infection. Poor hygiene can lead to infections such as Staphylococcus aureus, hepatitis B and C, and in rare cases atypical mycobacterial infections. These risks increase when equipment is not properly sterilized or when aftercare instructions are not followed closely. One of the biggest challenges in assessing tattoo toxicity is the lack of consistent regulation. In many countries, tattoo inks are regulated far less strictly than cosmetics or medical products, and manufacturers may not be required to disclose full ingredient lists. Although the European Union has introduced stricter limits on hazardous substances in tattoo inks, global oversight remains uneven. For most people, tattoos do not cause serious health problems, but they are not risk free. Tattoos introduce substances into the body that were never designed for long-term residence in human tissue. As tattoos become larger, more numerous, and more colourful, cumulative chemical exposure increases, especially when combined with sun exposure, aging, immune changes, or laser removal.Inked for life, informed for life

Tattoos remain a powerful form of self-expression, and current evidence does not point to widespread danger. At the same time, growing research highlights important unanswered questions about toxicity, immune effects, and long-term health. A tattoo may heal on the surface within weeks, but the ink remains part of your immune landscape for life. Being informed does not mean avoiding tattoos altogether. It means understanding that tattooing is a biological process as much as an artistic one. Asking about ink composition, choosing reputable artists, protecting tattoos from excessive sun exposure, and paying attention to delayed skin reactions can help you make choices that respect both personal expression and long-term health.Some of the links I post on this site are affiliate links. If you go through them to make a purchase, I will earn a small commission (at no additional cost to you). However, note that I’m recommending these products because of their quality and that I have good experience using them, not because of the commission to be made.

JOIN OVER

JOIN OVER

Comments